Reflections on human destruction, nature’s suffering, and the slow collapse of a fragile world.

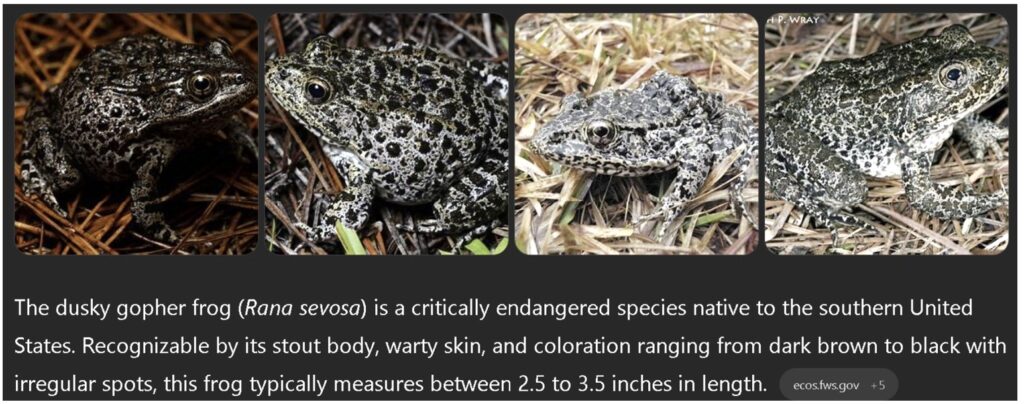

Dusky Gopher Frog: Fewer Than 200 Remain—Louisiana Restoration Offers Hope

SUMMARY: The dusky gopher frog (Rana sevosa), a critically endangered species with fewer than 200 individuals left, relies on ephemeral ponds and longleaf pine forests for survival. After a years-long legal battle, a real estate developer ultimately prevailed when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that land must be actual habitat to be designated as “critical habitat,” leading to the removal of protections on private land in Louisiana.

BACKGROUND: The dusky gopher frog’s situation is precarious. Historically found in Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi, its population has plummeted due to habitat loss, and remaining wild populations are now confined to a few locations in southern Mississippi (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; The Nature Conservancy).

In Weyerhaeuser Co. v. United States Fish and Wildlife Service (2018), the Supreme Court held that for land to be designated as “critical habitat” under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), it must first qualify as “habitat” for the species. The Court sent the case back to the Fifth Circuit to determine whether the Louisiana tract met that standard (see summaries on Ballotpedia and Justia).

In 2019, a consent decree between the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and the landowners removed the critical-habitat designation from the Louisiana site. This settlement allowed the landowners, including Weyerhaeuser Company, to retain control of the property without the restrictions that come with ESA critical-habitat status (Pacific Research Institute).

As of March 2025, conservation efforts continue. The Nature Conservancy (TNC), FWS, and the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries are preparing sites in Louisiana—such as the Talisheek Pine Wetlands Preserve—for potential reintroduction of the dusky gopher frog. These projects focus on restoring longleaf pine woodlands with seasonal wetlands, the exact habitat the species needs to survive (The Nature Conservancy).

Balancing economic development with conservation remains a complex challenge. While the legal outcome favored the landowners, ongoing restoration work offers a narrow but real hope for the dusky gopher frog’s future in Louisiana.

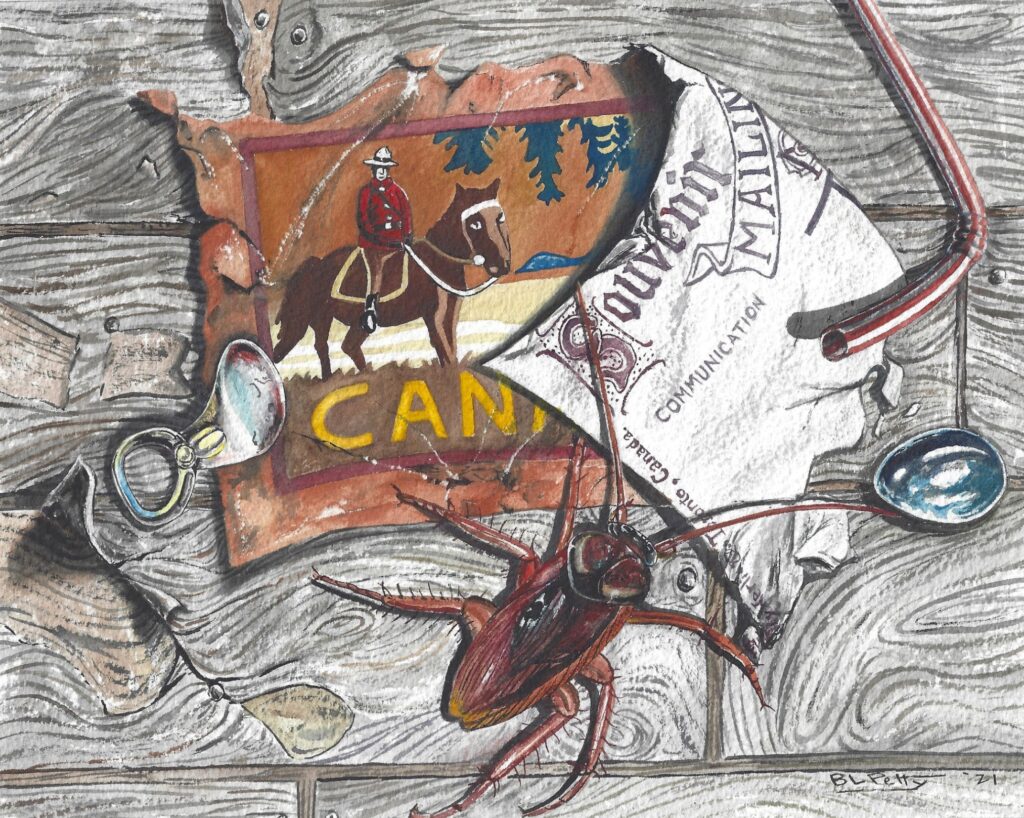

British Columbia 1,800 Species at Risk

SUMMARY: Approximately 1,800 species in British Columbia are at risk, highlighting the urgent need for conservation initiatives to protect the province’s rich biodiversity.

BACKGROUND: British Columbia (BC), Canada, is home to numerous species facing the threat of extinction due to factors like habitat loss, climate change, and human activities. Here are three of the most endangered species in the region:

1. Northern Spotted Owl (Strix occidentalis caurina): Once numbering over 1,000 individuals in BC, the northern spotted owl population has plummeted due to extensive logging of old-growth forests, their primary habitat. As of 2021, only three individuals remained in the wild in Canada, with conservation efforts focusing on captive breeding to prevent extinction. en.wikipedia.org

2. Southern Mountain Caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou): This distinct population of woodland caribou has experienced significant declines across Canada. Factors such as habitat fragmentation from industrial activities and increased predation have contributed to their endangered status. Conservation measures are ongoing to protect and restore their habitats.

3. Marbled Murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus): This small seabird relies on old-growth forests for nesting and is listed as threatened under Canada’s Species at Risk Act. Habitat loss from logging poses significant risks to its population. Protected areas, such as the Scott Islands Marine National Wildlife Area, provide critical nesting and feeding habitats.

For a comprehensive list of endangered species in British Columbia and detailed information on conservation efforts, you can visit the Government of British Columbia’s Species and Ecosystems at Risk webpage.

Smokehouse Season, Interrupted: What Reservoirs Really Take

SUMMARY: Hydro corridors promise “reliable power.” On the ground, they pause smokehouse seasons, drown traplines, and turn fish camps into waiting rooms. This isn’t abstract. It’s water quality, fat on the fish, hands that have no work in June, and elders who must drive past their own river to buy store salmon wrapped in plastic. I keep hearing the same list: what the valley gave, what the reservoir took, and what never returns.

BACKGROUND: Reservoirs don’t just flood—they re-write calendars. Spring break-up arrives different. Shorelines slip. Ice forms later, thinner. Boat launches move. The stable places where nets once set clean become snag fields and weed mats. A “shoreline” that used to be a path is now a moving target.

LOSSES, NAMED:

• Clean water that doesn’t bloom green in July.

• Intact fish runs that hit their marks like clockwork.

• Smokehouses lit on time, not “when the lake lets us.”

• Traplines and trails that used to survive a thaw.

• Burial grounds left where the stories put them.

• Language tied to seasons, not shift schedules.

• The right to decide what happens on the river that feeds you.

INDIGENOUS LIVELIHOODS: When smokehouses go quiet, it’s not just food security. It’s ceremony, teaching, and cash-work lost—guiding, selling fish, fixing nets, fueling boats. “Relocation benefits” don’t replace the map in your head: the bend where grayling stage, the eddy where whitefish sit, the shallow where kids learned to read current the way others read print.

ECOLOGICAL COSTS:

• Reservoir methylmercury climbs the food chain; “catch and release” becomes the rule where “keep and smoke” once was.

• Microclimates shift around big lakes; late frosts bite gardens and berry patches; summer water warms into algal scum.

• Beaver ponds drain or disconnect; muskrats thin; ducks skip traditional brood water.

• Moose and caribou routes break—shorelines and crossings they used for generations now lead into open water or impassable brush.

• Salmon (or trout/whitefish) runs shrink to rumor; spawning gravel silts over; tributaries cut new channels that ignore old wisdom.

HUMAN COSTS:

• Income drifts from fishing, guiding, and land skills toward corridor jobs—flagging, security, hauling. When the project ends, so does the paycheck.

• “Move to town” becomes policy shorthand for opportunity. But off-reserve, most tax exemptions vanish; rent arrives every month; the river becomes a weekend drive, not a larder.

• Grief shows up as “choice”: take the job or keep the camp. Families split the difference and lose both.

WHAT WORKS (WHEN WE LET IT):

• Corridor reroutes that honor fish staging sites, burial grounds, and beaver complexes.

• Drawdown rules that protect spawning windows and keep near-shore water from yo-yoing.

• Local water monitors paid year-round—elders and youth logging turbidity, temperature, and blooms.

• Procurement that favors boat shops, smokehouse suppliers, and on-river guides—keeping money in the current, not on the highway.

• One simple test before any vote: “Drink from the water you plan to manage.” If that sentence makes a boardroom flinch, the plan isn’t ready.

WHY IT MATTERS: A corridor that delivers steady megawatts and unstable lives is not success. If the valley can’t smoke fish, if the graves move, if the river turns to something you visit instead of something that feeds you, the balance is gone. Stewardship isn’t “power on.” Stewardship is “smokehouse on, too.”

CALL TO ACTION: Keep smokehouse calendars intact when you draw project ones. Fund monitoring by the people who read the river best. Respect a “no” when the map crosses a memory. Power that erases place isn’t clean. It’s just quiet.

The River Eats the Road: Permafrost Slumps and the Cost of “Maintenance”

SUMMARY: Northbound highways and access roads look fixed until spring returns. Permafrost softens, banks slump, culverts choke, and the river pulls the edge back into itself. We call it “washout repair.” The river calls it gravity and heat. I keep thinking: we treat symptoms with gravel when the diagnosis is thaw.

BACKGROUND: What’s failing isn’t just asphalt; it’s ice-rich ground that once stayed frozen long enough to hold the grade. Survey lines, new ditches, and heat from dark road surfaces speed the melt. Water finds the easiest path, undercuts the fill, and turns a hairline crack into a throat that swallows trucks.

WHAT IT LOOKS LIKE ON THE GROUND

• Shoulders shear off in long crescents; the guardrail hovers, then drops.

• Ditches become creeks; culverts silt and “perch,” blocking fish passage.

• Detours creep closer to the bank each season as the cut widens.

• Bridges “heave” at the ends; frost boils rut the approaches.

• The same orange cones return to the same kilometer markers—every year.

INDIGENOUS IMPACT

• Traplines and smokehouse runs stall when a single failing culvert blocks the only crossing.

• School, clinic, and store trips stretch by hours or days when “temporary” closures become the season.

• Safety nets shrink: a breakdown on a half-closed road is not the same as help in town.

• Corridor crews get paid; camps lose money and time waiting for the road to reopen.

WHY “MAINTENANCE” MAKES IT WORSE

• Repeated “top-ups” of warm, dark gravel absorb heat and deepen the thaw.

• Undersized culverts speed water like a fire hose, scouring beds and banks.

• Straight ditches deliver meltwater faster than the valley can handle.

• Patchwork fixes keep the ledger off the project budget and on the land.

WHAT WORKS (WHEN WE LET IT)

• Build light, not hot: pale aggregates, geotextiles, and venting layers that keep cold in the ground.

• Oversize and fish-friendly crossings: multi-cell culverts or short spans that let water, fish, and ice move without tearing banks.

• Set back from rivers: choose the hill line over the cutbank whenever the map allows.

• Seasonal weight rules that follow the thaw, not the calendar.

• Local monitors paid year-round to log slumps, culvert blockages, and early warning signs.

• One hard promise: every “temporary” fix gets a date for a permanent solution—or it isn’t called fixed.

MEASURE IT, FUND IT, RESPECT IT

“Maintenance” that returns like spring breakup isn’t maintenance; it’s a bill the river keeps sending back. If a road serves a fish camp, a smokehouse, a clinic, or a school, the crossing is not an optional line item. Put the money where the thaw already is—where the river eats the road—and build as if you plan to apologize to the valley for nothing.

These laments live between the novels—where the real world shows what the stories are warning us about.